Concepte actuale de identitate neactualizat, de Alex Kuch

Adoptarea este un proces complex și una dintre provocările cele mai complexe în jurul adopțiilor este identitatea unui individ. Idei în jurul identității în adopțiilor au o varietate de puncte de vedere, chiar și instituții internaționale recunoscute, o astfel de UNICEF și Organizația Națiunilor Unite au luat pe opinii în care sugerează că, în special identitatea este limitată la locul geografic al nașterii unui individ, prin urmare, în (Declarația din drepturile copilului, 1959). Prin urmare, aceste organizații în ansamblu a ales să interpreteze toate cele 10 de articole, acei copii care au nevoie să rămână în țara lor de naștere. Ei consideră identitatea ca un concept static, în timp ce identitatea este construită social și este format de către individ și interacțiunile cu alte persoane a lungul timpului.

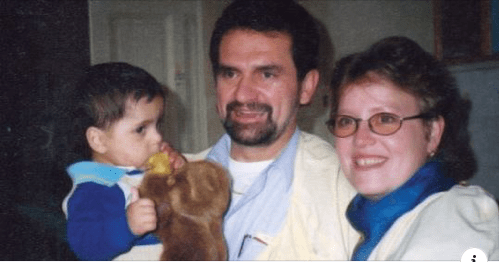

Această socio – autobiografie va analiza modul în care conceptele de identitate în special în căutarea sinelui de sticlă, ME și eu și racializing și modul in care fortele sociale mi-au modelat pentru a fi persoana care sunt acum si va investiga importanța sociologică a conceptelor.

Charles Horton a venit în lucrarea sa (Cooley, 1902) cu conceptul de sticlă auto în căutarea. Acesta conține trei concepte cheie; ne imaginăm cum se pare o altă persoană. Am la un nivel personal se poate referi cu siguranță la faptul că, mai ales din cauza romilor meu sau informal cunoscut sub numele de etnie țigănească, ceea ce îmi dă un ton mai inchisa a pielii. Ca urmare a acestui fapt îmi imaginez că cei mai mulți oameni care mă văd prima dată că, din cauza aspectului meu va crede că eu sunt de la una din următoarele țări, Orientul Mijlociu, India, Mexic sau Spania sau alte țări care sunt considerate a fi tonul pielii ofmy. Acest lucru este sprijinit în diferite cele mai noi cercetători, cum ar fi (Perkins, K, 2014), modul în care primul și al doilea imigranți simțit în Statele Unite.

De asemenea, ne imaginăm modul în care alții judeca aspectul cele. Toată lumea face acest lucru și mai ales cei care sunt marginalizați în societate. Acest lucru se întâmplă între diferitele culturi și de ori.

Eu personal am experimentat modul în care mi-am imaginat alții m-ar judeca, după ce a fost la televiziunea națională română și vorbesc despre povestea vieții mele și iertător mama biologică pentru mine abandonarea. M-am așteptat să fie șocat despre comportamentul meu pentru că am comportat într-un mod care a fost contra-cultură. Studii (Tice, D, 1992) au arătat că un comportament în public a avut un efect asupra modului greater- o imaginează sine și anticiparea unor viitoare întâlniri publice a crescut interiorizarea. Acest lucru cu siguranță a fost cazul pentru mine.

Dar nu am imagina că oamenii ar găsi în loc, de asemenea, o formă de confort în acțiunile mele, în special cei care au abandonat copiii lor și le-a dat la orfelinate, au existat numeroase cazuri în care persoanele în vârstă, în public exprimat acest lucru pentru mine. În cercetare, sa demonstrat că modul în care alții sunt vizualizate și efecte cum se simt cu privire la această hotărâre percepută (Shrauger, J, 1979) & (Aken, M, 1996) judecat.

De asemenea, ca urmare a hotărârii percepute afectează felul în care se simte despre ei înșiși, eu cu siguranță pot spune că m-am simțit copleșită de modul în care ma judeca oamenii din România într-un mod pozitiv și într-o oarecare măsură, chiar mi-a dat celebritate / statutul sfânt , cum ar fi oamenii cer să vorbească cu mine în public și cu o fotografie făcută cu mine. După cum sa menționat mai sus, studiile confirmă faptul că interacțiunea mai publică și anticiparea acest lucru crește interiorizarea, prin urmare, aceasta crește, de asemenea, modul în care s-ar simți hotărârea percepută (Tice, D, 1992)

Aceste tipuri de evenimente nu se întâmplă doar pentru mine ca individ, ci se întâmplă cu alte persoane, precum și care au fost în situații similare, în ciuda fiind influențate de diferite forțe sociale și diferite perioade de timp.

Conceptul de sticlă în căutarea auto-are o importanță sociologică enormă, mai ales în exemplul meu cum se simt adoptees despre ei înșiși, ca urmare a hotărârii percepute altora, prin urmare, un argument foarte de bază se poate face ca societatea ar trebui să fie informați cu privire la adopții și modul în care oamenii mai ales ar trebui să fie vorbit pentru toate părțile implicate și modul în care aceasta poate afecta și de a face oamenii se simt. Un studiu foarte recent (Eriksson, P, 2015) arată că părinții adoptivi sunt foarte mulțumiți de educație pre-adopție și în timp ce adoptarea a avut loc și este un proces foarte important.

George Herbert Mead în (Mead, G, 1982) a venit cu conceptele de mine și I, „I“ este o persoană care face parte independentă care opereaza inainte de un individ este conștient de faptul că există lumea din afara propriei lor de sine. „Eu“ este ca urmare a influenței altor persoane în societate.

Pentru mine personal am început să fie conștienți de faptul că există lumea din afara propriei mele de sine, la vârsta de 4 ani. Cercetare (Bloch, H, 1990) arată că acest lucru se întâmplă la vârsta este de 2 ani, dar începe de la vârsta persoanei se naște până la vârsta de 5 ani. Cu toate acestea (Cooley, 1902) susține că indivizii imagina cum lor de auto-aspect este judecat de către alții, dar acest lucru în mod clar nu este cazul pentru copii sub vârsta de 2, dar varys desigur si nu imagina cum este judecat aspectul lor și prin urmare, nu au un sentiment perceput de această hotărâre. Acest lucru poate fi văzut în mod clar de către copiii mici, deoarece, în general, pe cont propriu ei nu judeca unii pe alții și nu se simt judecat. Eu personal pot spune că la vârsta înainte de unul este conștient de lumea exterioară de sine lor. Cu toate acestea, după vârsta de 2 Me într-un individ ca (Mead, G, 1982) prevede este un rezultat al influențelor altor oameni în societate. Eu personal cu siguranță pot spune că pentru mine am fost mai mult influențat de familie și prieteni apropiați mai în vârstă am. Acest lucru este confirmat și de (Cooley, 1902) că, ne imaginăm cum alții vedea, judeca aspectul cuiva și, ca urmare au un sentiment perceput despre judecata făcută pe o persoană.

Rasializarea este o practică comună și noi toți au experimentat-o și a făcut-o noi înșine. (Matthewman, S, 2013) definește rasializarea ca fiind „procesul prin care idei și credințe despre rasa, impreuna cu clasa si sex, forma relațiilor sociale; cu alte cuvinte, construcția socială a rasei.“Sau (Matthewman, S, 2013) definește rasializare ca„un proces social prin care „un grup este clasificat ca fiind o rasă și definită ca o problemă“

Am de multe ori cu experiență rasializarea mai ales că oamenii judecă cel mai adesea în cazul în care sunt de aspectul meu fizic și oamenii sunt cu adevărat șocat când le spun că sunt din Europa și adoptat de România de către părinți germani. Există aceste diferențe în ceea ce privește rasa si origine etnica.

.

| Rasă |

Etnie |

| Moștenit – fizică |

Învățate – Social |

| Științific |

Subiectiv |

| Văzut |

Simțit |

| Proiectat |

Ales |

| Clasificare |

Identitate |

| Fix |

Fluid |

| Colonialism |

Post-colonialismului |

Tabelul de mai sus prezintă câteva diferențe esențiale între rasă și etnie.

O caracteristică generală cheie este faptul că etnia este fluid și dinamic; Cu toate acestea, o mulțime de organizații internaționale susțin că o adopție internațională (adopțiile internaționale) daune identității adoptatului lui. Cu toate acestea, identitatea unei persoane nu depinde de țara de naștere, ci un factor, cum ar fi ceea ce a învățat în creștere și identitatea unei persoane se schimbă continuu și în curs de dezvoltare în timpul vieții lor.

Chiar și oamenii pot avea mai multe sau chiar un mix etniile, prin urmare, pot să mă numesc un român, german, neozeelandezul (kiwi) și până de curând în acest an nu ar lua în considerare România una dintre etniile mele, dar evenimente dramatice, cum ar fi sa se confrunte cu familia biologică dar chiar și mai inspectează orfelinate și aziluri mi-a dat o mai mare înțelegere în trecutul românesc și prezent și în formă de identitatea mea personală.

Conceptul de racializing are o importanță imensă sociologică pentru că noi toți judecăm pe alții de numeroși factori, cum ar fi etnia, credințele religioase și aspectul. Ca urmare a acestei anumite percepții iau în evidență și să dea naștere la putere a oamenilor se afirmă în detrimentul altora. Un exemplu în acest sens pentru mine a fost că, atunci când am fost adoptat, un unchi a spus „Voi adopta Alex, cum nu știi că el nu va deveni un hoț / criminal“, care a fost rasializarea pentru că am fost din România și va fi adoptat , care a avut și are încă un stigmat rău în ceea ce privește crima. În ciuda faptului că eu fost în România de mai multe ori în diferite părți, nu am mai experimentat nici o crimă și a fost tratat cu cel mai mare respect.

Prin urmare, în rezumat identitate este un concept complex, mai ales în Adopții. Cu toate acestea, argumentele de la instituții, cum ar fi Organizația Națiunilor Unite și în special UNICEF, care daune adopțiile internaționale cauze la identitate ca urmare a unei persoane părăsesc țara de naștere este un punct bazat foarte rasial de vedere și a identității ca puncte de vedere fixe. Cu toate acestea identitatea constau în mult mai mult, cum ar fi discutat mai devreme Me și eu, sinele individuale și influența sinelui de către societate. Looking Conceptul de sticlă de sine în cazul în care punctele de vedere, percepția și judecățile altora afectează căile unui individ se raportează la el sau ea.

Ceva ce ar fi bine pentru a investiga ar fi pentru aceste organizații să facă mai multe cercetări calitative și cantitative în modul în care, de fapt, în instituțiile mele orfelinate de caz, efecte de copii sau să se uite la cercetare existente, deoarece acestea nu sunt soluții permanente pentru copii pe termen lung.

Pe lângă faptul că rasializarea este foarte critică și aceste instituții susțin adesea că anumite etnii sunt mai problematice decât altele, dar nu este etniile, dar modul în care indivizii au fost tratate; prin urmare, experiențele lor personale, care formează identitatea lor, care de multe ori au fost de natură psihologică și fizică.

Prin urmare, în general pentru mine identitatea mea a fost afectată de adopție, dar și-a extins experiențele mele personale și de fapt îmi permite să interacționeze mai bine cu oameni de diferite etnii, din cauza gama mea de experiențe.

numărul de cuvinte: 1619

Referințe

Aken, M., Lieshout, A., & Haselager, G. (1996). Competența adolescenților și reciprocitatea de auto-descrieri și descrieri ale acestora furnizate de către alții. Jurnalul Tineretului și Adolescence, 25 (3), 285-306.

Bloch, H. & Bertenthal, BI (1990). Senzitivomotor Organizații și Dezvoltare în pruncie și timpurii Proceedings din copilarie de cercetare NATO avansată Atelier de lucru pe senzitivomotor Organizații și dezvoltare în fază incipientă și timpurie copilarie Chateu de Rosey, Franța (seria NATO ASI Seria D, comportamentale și științe sociale;. 56) . Dordrecht: Springer Olanda.

Cooley, & Aut. (1922). Natura umană și ordinea socială .

Eriksson, P., Elovainio, M., Mäkipää, S., Raaska, H., Sinkkonen, J., & Lapinleimu, H. (2015). Satisfacția părinților adoptivi finlandezi cu statutară consiliere pre-adoptare în adopțiile internaționale. Jurnalul European de Asistență Socială, 18(3), 412-429.

Matthewman, S., Vest-Newman, Catherine Lane, & Curtis, Bruce. (2013). Fiind sociologică (2nd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mead, G., & Miller, David L. (1982). Individul și sinele social: opera lui George Herbert nepublicata Mead . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Perkins, K., Wiley, S., Deaux, K., & Zárate, Michael A. (2014). Prin care Looking Glass? Surse Distinct de respect public si respectul de sine Printre Imigranti primul si a doua generație de culoare. Diversitatea culturală și etnică Psihologie minoritare, 20 (2), 213-219

Shrauger, J., Schoeneman, T., & Hernstein, R . J. (1979). Vedere interacționistă simbolică a conceptului de sine: prin oglindă întunecat. Psychological Bulletin, 86 (3), 549-573.

Tice, D., & Miller, Norman. (1992). Auto-Concept Schimbarea și auto-prezentare: Looking Glass Sinele este de asemenea o lupa. Jurnalul de Personalitate și Psihologie Socială, 63 (3), 435-451.

Adunarea Generală a Organizației Națiunilor Unite Sesiunea 14 Rezoluția 1386 . Declarația drepturilor copilului A / RES / 1386 (XIV) 20 noiembrie 1959. Adus de 2015-10-29.

Hope and Homes for Children is working to close the institution where Johnny lives by finding safe and loving family-based care for all the children living there. The news that EU funding is now available to support this and 49 other closure programmes marks a significant step towards the day when all children in Romania can grow up in families and not in orphanages.

Hope and Homes for Children is working to close the institution where Johnny lives by finding safe and loving family-based care for all the children living there. The news that EU funding is now available to support this and 49 other closure programmes marks a significant step towards the day when all children in Romania can grow up in families and not in orphanages.