When Love Changes Everything

Alex Kuch was only eighteen years of age when he spoke at the Romanian Parliament about re-opening International Adoptions from Romania

25 October 2018.

The love and care of his adoptive parents changed the world for Alex Kuch, but he also gives credit to the University of Auckland, which “opened up so many opportunities” to learn and then to apply the knowledge he has gathered.

The story of Alex Kuch, a recent University of Auckland graduate in Politics and International Relations, begins half a world away in an orphanage in Cluj-Napoca, Romania.

Given the basics of life but deprived of any affection, warmth, stimulation or love, Alex suffered from a condition called hospitalisation.

He habitually rocked, had no language and could not make eye contact with another human being.

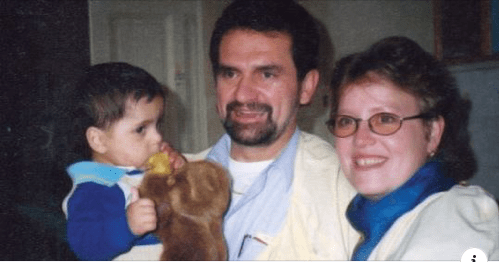

His life changed forever when his adoptive parents Heidi and Walter Kuch rescued the 18-month-old and gave him a second chance at life in Germany, later relocating to New Zealand when Alex was 11, attracted by our education system.

“When I met Alex he was very quiet,” Walter says, as he recalls the “basic and overcrowded” institution where some 200 children were housed.

“He had a black mark on his cheek. We were told it was from another child who bit him when he tried to pinch an apple. There was not enough for them to eat so they fought over food. Alex couldn’t walk. Nobody cared for him.”

Walter bundled Alex up and took him to Bucharest for three nights while paperwork was finalised, while his new mother Heidi waited anxiously in Germany for their arrival.

“On the first morning in our hotel he woke up and I dressed him and he started rocking. That was a scary moment, it was a symptom of hospitalisation. We didn’t know if he would recover, but regardless I thought ‘he is our child and I will take him home’.”

After a few weeks in a loving home with responsive parents, the rocking stopped and never came back. But the long-term outlook for Alex was grim. A psychologist advised that he would never lead a normal life, complete high school, or have the social skills to integrate into society.

With the help of intensive speech and fine motor therapy, Alex walked at 22 months and began to talk around the age of five.

This year Alex completed a Bachelor of Arts degree and is now an accomplished public speaker, researcher and adoption advocate.

My parents weren’t going to let a prediction determine who I was going to become.

“My family is really proud of me, especially as I’m the first person in my family to have gone to university. It has been challenging; however the University has been very supportive. I had a writer for exams as I still have some fine motor challenges such as not being able to write neatly and quickly. But coming to university has opened up so many opportunities for me.”

Alex’s full list of achievements is lengthy and constantly growing. Standouts are speaking twice in Romania’s parliament, the first time when only 18 years old, being named a finalist for Young New Zealander of the Year, and completing research looking at the experiences of adoptees.

He is also an advocate for re-opening Romania’s borders to international adoptions. After the overthrow of the Ceau?escu government in 1989, thousands of abandoned children were adopted by overseas families, but corruption was rife and the world’s attention was drawn to the terrible conditions. Romania closed its borders to international adoptions in 2001.

“Just because there have been bad instances, entire countries have closed international adoptions as a result.

It’s like saying just because a small proportion of a population has inflicted violence towards children then everyone should be prevented from having children. What we need is to develop better policies to protect children during the adoption process.”

To this end, Alex is helping to establish a framework for global adoption policies at the third Asia-Europe Foundation Young Leaders Summit on ethical leadership, and will work with other global adoption experts at the International Conference on Adoption Research in 2020 in Milan.

He will also share his joint research with Dr Rhoda Scherman from AUT, which compiles the experiences of other adoptees published on the New Zealand based ‘I’m Adopted’ website.

“I’m Adopted is a place where adoptees from around the world can connect and share their stories,” says Alex. “With the permission of the adoptees, we have gone through dozens of stories to pull together the common themes of what adopted children go through. It’s valuable knowledge for agencies and families, for example knowing when to intervene or what to expect, and to provide better support.”

In an unusual twist in Alex’s own story, he met his birth mother three years ago on a live Romanian talk show.

Alex has visited Romania twice to advocate for reopening international adoptions, but has never sought to connect with his birth parents. While he was speaking on television about his advocacy work, the show’s producers blindsided him by bringing his birth mother and half siblings onto the stage.

“It could have been done more professionally, but things are a bit different over there,” Alex says.

“After I visited some orphanages and was then surprised by my biological family, I began to recall some visual impressions of my time in my orphanage. It was very emotional.”

Alex has chosen not to stay in contact with his birth mother.

“Why would I? I have a mother and father in New Zealand,” he says.

Heidi, his adoptive mother, says there was never an expectation that Alex would attend university. His younger brother Colin, also adopted from Romania two years after Alex, is more hands-on and has started a building apprenticeship.

“Alex just loves to learn. Once he learnt to talk, whoosh, it was like a waterfall that never stopped. He was always asking questions,” Heidi says.

“But we never put pressure on him to go to university. We just supported him in whatever he wanted to do. We didn’t spoil the boys or give them lots of toys, but we spent lots of precious time with them playing games and doing activities as a family.”

But Heidi says Alex was a challenging student and the German schooling system held him back.

“The New Zealand school system has been very good for Alex. When they discovered he was good at maths they pushed him, and then he was away.”

Alex was a top student at KingsWay School, on the Hibiscus Coast where he grew up.

Now back living in Europe, he has begun an internship with children’s rights and development organisation, Aflatoun International, based in the Netherlands. He also plans to return to Romania to continue to advocate for the re-opening of international adoptions, and is writing an autobiography chronicling his journey from the orphanage to New Zealand.

“Alex’s background, interests and experience will help us to scale up our focus on children that are living in alternative care and will have to stand on their own feet as they reach the age of 18,” says Roeland Monasch, director of Aflatoun International. “We want to make sure this specific group of children are empowered with these essential social and financial skills in order for them to be resilient and successful in their adult life. Alex will be a great resource for us.”

By Danelle Clayton

#love

Ingenio: Spring 2018

This article appears in the Spring 2018 edition of Ingenio, the print magazine for alumni and friends of the University of Auckland.

Romania’s Last Orphanages

http://www.hopeandhomes.org/news-article/economist-film/

@TheEconomist has visited @HopeandHomes projects in Romania to create a film examining how we’re finding families for the 7,000 children who remain in ‘Romania’s Last Orphanages’ https://buff.ly/2nn16YQ #FamiliesNotOrphanages

Hope and Homes for Children’s work in Romania is central to a hard-hitting new film, released today by The Economist.

Available here. ‘The End of Orphanages?’ focuses on the transformation that’s taken place in Romania’s child protection system in recent decades.

Viewers are reminded of the horror of the Ceausescu-era orphanages that were discovered after the fall of the dictator in 1989 and goes on to explain how the majority of the county’s orphanages have now been closed by ensuring that children can grow up in family-based care instead.

Hope and Homes for Children has played a fundamental part in driving the process of child protection reform in Romania over the last 20 years. When we began work there in 1998, over 100,000 children were confined to institutions. Today that figure has fallen by more than 90% to less than 7,200.

The Economist film tells the story of Claudia, a woman in her late 30s who was born with one arm and abandoned to the orphanage system as a baby. She shares painful memories of the abuse and neglect she suffered as a child. She struggles to remain composed as she describes one incident where she was stripped and beaten with a rope as a punishment for playing in the wrong place.

“Effectively we belonged to no one. You were basically treated like an animal” she says.

Today Claudia works in the Ion Holban institution in Iasi County – one of the remaining orphanages that Hope and Homes for Children is working to close in Romania. The film shows some of the children who have already been supported to leave the institution and join families.

The Manole sisters spent five years in Ion Holban after their remaining parent died. Our team gave their extended family the extra support they needed to make it possible for all four girls to leave the orphanage and begin a new life together with their Aunt and Uncle.

Stefan Darabus, our Regional Director for Central and Southern Europe, contributes to the new film, explaining “Any institution like Ion Holban should be closed. They do not offer family love. They do not offer what a child needs most which is to belong to a family, to have a mother and a father, to feel special.”

The film gives a balanced view of the process of deinstitutionalisation, pointing out the risks to children if the process is not properly supported but gives the last word on the future of the children in the Ion Holban to Claudia. “What they need is such a simple thing,” she says. “Parental love in the bosom of the family, rather than in the bosom of the State. But mainly they need to be accepted.”

Hope and Homes For Children; Romania. Deinstitutionalisation

In 2018, almost 6,500 children in Romania still live in institutions, which are inappropriate for their development.

In 2018, almost 6,500 children in Romania still live in institutions, which are inappropriate for their development.

Reports of sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, child-trafficking and suicide, consistently appear in the media regarding the abandoned children in these institutions.

Over the past twenty years, Hope and Homes for Children, Romania, has closed 56 institutions, including the Nassau Foster Centre, and built and moved institutionalised children to one hundred and four family type homes.

http://www.hopeandhomes.org/news-article/mark-and-caroline-romania-honours/

Romanian Adoptee Defies The Odds To Complete A Degree

When Romanian orphan Alex Kuch was adopted at age two, his new family was told he would never finish high school or lead a normal life.

This week, Alex finished his final semester of a Bachelor of Arts degree in Politics and International Relations with a minor in Sociology at the University of Auckland.

Now 23-years-old, Alex is an established children’s rights advocate and is invited to speak around the world. Next month, he will co-present research into the experiences of adoptees at a major international conference in Canada.

“My parents weren’t going to let a prediction determine who I was going to become,” Alex says. “While never pushing me, they always encouraged me to give my best in everything I did. My family is really proud, especially as I’m the first person in my family to go to university. I’m really looking forward to using my degree in the real world.”

Alex will be one of the youngest presenters at the sixth International Conference on Adoption Research in Montreal and has received a grant from the University of Auckland’s Vice-Chancellor’s Student Support Fund to attend.

His research, completed with Dr Rhoda Scherman from AUT, analyses the stories of other adoptees shared on the New Zealand-based I’m Adopted website.

“The stories have helped us to pull together the common themes of what adopted children go through. It’s valuable knowledge for agencies and families, for example knowing when to intervene or what to expect, and to provide better support.”

Alex was adopted in 1997 from an orphanage in Cluj- Napoca, Romania by a German couple. He also has a younger brother adopted by the same family. The family moved to New Zealand in 2006.

At the time of his adoption, a German psychologist advised Alex’s family that the emotional damage from spending his formative years in an orphanage meant he would never lead a normal life, complete high school, or have the social skills to integrate into society.

“The conditions weren’t the greatest. My parents were told that I had started to rock backwards and forward due to a lack of emotional and physical stimulation and I could not look people directly in the eyes.”

Alex received specialist support such as speech and fine motor therapy, and against all odds, has now completed high school and university.

“It was challenging, however the University of Auckland has been very supportive. I had a writer for exams as I still have some fine motor challenges. Also many of my assignments were tailored to reflect my advocacy work.”

Alex is passionate about lobbying the Romanian Government to re-open international adoptions, which were closed in 2001.

In an unusual twist, Alex met his birth mother on live television during a lobbying trip to his birth country. While speaking on a talk show about his adoption experience, producers blindsided him by bringing his birth mother and half siblings onto the stage.

Alex is now concentrating on his long-term aspiration is to establish a children’s rights consultancy that collaborates with different sectors to have a positive impact on the wellbeing of children.

In October Alex will speak in Brussels at the third Asia-Europe Foundation Young Leaders Summit on children’s rights and international adoptions.

Danelle Clayton | Media Adviser

Communications Office

Email: d.clayton@auckland.ac.nz

Blue Heron Foundation; Scholarships for Orphaned and Abandoned Romanian and Moldovan Youth

Blue Heron Foundation; Breaking the Cycle of Poverty.

Blue Heron’s Foundation mission is to improve the quality of life for orphaned and abandoned institutionalized youth in Romania and Moldova by providing them with Scholarships for a College education.

In the past twenty years, the Foundation has successfully helped three hundred and fifty students achieve their dream of a College education.

The enrolment period for scholarships is- 1st. May- 31st. August.

Blue Herron Foundation covers – Tuition fees.

Provides a monthly amount of money for personal expenses.

Provides access to a mentoring program.

Free participation in the Summer Camp.

http://www.blueheronfoundation.org. Florin with his Bachelors in Marketing and Management.

Since 2002 the Blue Heron Foundation has dedicated its efforts to improving the quality of life of Romania’s orphaned and abandoned children by providing them with greater access to life’s opportunities. The organization awards them scholarships, training courses, mentors and counselling throughout their collage years. 100% of the donations go directly to the project as the founders cover all organizational expenses.

R. Todd Updegraff.

The Journey Home Made Me Complete; John Gauthier

MILWAUKEE —A Milwaukee-area man who was adopted from an orphanage in Romania when he was 5 years old found some answers this summer in a journey that, for him, proved you can go home again.

John Gauthier, 32, grew up outside Milwaukee, but he always wondered about his birth family and the life he missed.

When he left for Romania in July, he went back to the land where he was born.

“I’ve been waiting for so long I just couldn’t wait any longer,” John Gauthier said.

Like thousands of other Romanian children, John Gauthier spent time in an orphanage. He was saved when a couple from the town of Lisbon saw their plight televised on 20/20.

They traveled to Romania in 1991 to adopt John and another boy and brought them to Wisconsin.

But John was always curious about home.

“It was something I knew was going to come along with time,” John’s father, David Gauthier, said.

Sensing his son’s curiosity, two years ago, David Gauthier gave John a letter.

“I open it, and it’s all in Romanian. I don’t know what it says. I remember that night I translated just the first sentence on the top of the letter and it said, ‘My dear son,'” John Gauthier said.

The letter said: “My dear son, when you read these lines that I am writing you right now, you will be an adult and maybe you are going to ask yourself, who are you? Where do you come from? Please do not judge me because I let you go. I just wanted you to have a better life than mine.”

The letter let John know who his mother was. With her name, through Facebook, he quickly discovered he had siblings in Romania.

“I just needed to go over there and see them,” John Gauthier said.

So this summer, he did.

He met his older brother, and for the first time, two younger sisters.

“They changed me in just seeing the beauty in everyone, just even more than what I saw before,” John Gauthier said.

He set foot in the village where he was born, Ramnicu Valcea, and met extended family he didn’t know he had.

“I thought about how much I could’ve experienced with my siblings, but I’ll take what I can get now. I’m just thankful for that,” he said.

Before he left, he went with his siblings to their mother’s grave. There, he showed them the letter that led him to them.

“The whole trip made me complete. The whole journey made me complete. I felt like I found my voice. I found myself and meeting them changed me forever,” John Gauthier said.

He hopes to travel to Romania again, and his father, David Gauthier, plans to take his other son, David, to Romania soon, so he can have the same kind of experience and discover his roots.

Shame of a Nation

Izidor Ruckel outside the locked orphanage in 1990.

Tortured For Christ (The Movie)- Official Trailers 1 and 2

Romania Reborn; Hands of Hope

She grew up during the darkest days of Communism, the daughter of a Pentecostal preacher. She remembers being mocked for her faith every day at school. She remembers peeking under her bedroom door at night, watching the boots of the soldiers who had come to take her father away for interrogation. She remembers what it was like when Communism finally fell, and she learned that the government had hidden hundreds of thousands of children away in terrible orphanages. And that was when Corina Caba knew what God wanted her to do with her life.

Photo- Corina Caba holding a malnourished baby.

She founded her orphanage in a tiny apartment in 1996, taking abandoned babies from the hospital and caring for them until she could find adoptive families. Gradually, she added to her staff, paying their salaries however she could. After Romania Reborn was founded to support the work, she built a bigger facility, hired more workers, and took in more babies. As the years passed, Romania’s laws and child welfare system evolved, but God always made a way for Corina to help abandoned children.

Today, Corina is the adoptive mother of four children and a mother figure to hundreds more, whose lives she has forever changed. She is also an emerging national leader in the field of orphan care, traveling to speak at conferences, helping advise the government on policy, and (reluctantly) speaking to national media. And she’s still fighting for individual children every day. “When the pain is too much, God taught me to trust in Him,” she says. “One day, He will restore all that seems lost, redeem all that seems hopeless, repair all that seems destroyed. Our God owns the last reply!”

http://www.romania-reborn.org/

#love